It’s a common scene in film and television; people jumping from their seats and springing to action with the Heimlich maneuver when a restaurant patron starts to choke. But how many bystanders would recognize someone whose heart has stopped? What about an overdose? Most people are willing to help in the event of such emergencies, but what if they don’t realize what’s happening?

This is the main message behind new research from a team led by CHÉOS Scientist Dr. David Barbic.

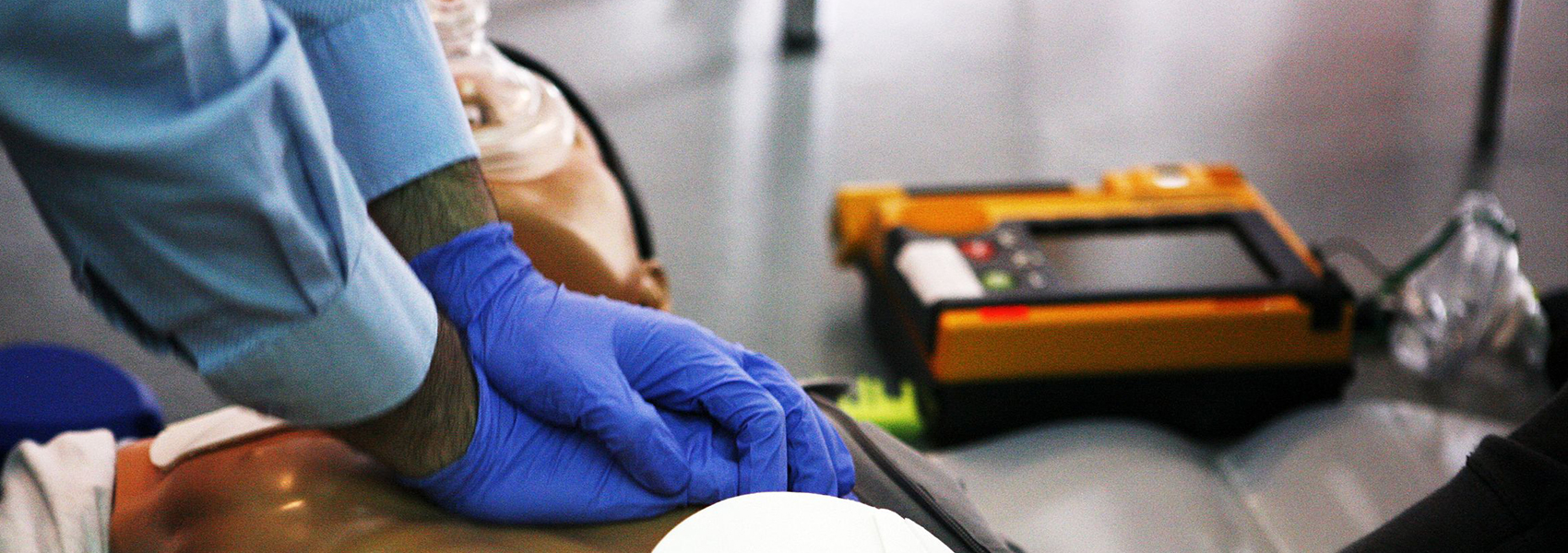

When a person’s heart or breathing stops, their survival largely depends on the immediate recognition and response of bystanders.

For every minute cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or defibrillator (AED) application is delayed, the chances of survival with good outcomes after a cardiac arrest decreases by 12%. For opioid overdose, bystander CPR and naloxone use significantly decrease mortality.

From a public health perspective, we spend significant money on training people to provide CPR and use AEDs. There have also been significant efforts to provide naloxone training around the province. However, the value of this type of training is dependent on people’s ability to recognize when they need to intervene.

To characterize the public’s ability to recognize cardiac arrest and opioid overdose, Dr. Barbic’s study team surveyed 234 participants in public locations in Vancouver, Victoria, Prince George, and Kelowna.

Participants were asked a series of questions about their background, history with CPR, AED, and naloxone, and knowledge and willingness around intervening. Respondents also viewed two video clips, one showing a person having a cardiac arrest and one demonstrating an opioid overdose. Participants were then asked to identify the medical emergency from a list of options, as well as how to intervene.

“We found that there was a considerable mismatch between what people were willing to do and their ability to recognize these emergencies,” said Dr. Barbic.

Though nearly half of the participants had past or current training in CPR, only 11% (26 people) correctly identified a cardiac arrest and 23% correctly said they would perform chest compressions. However, over half were willing to perform CPR or apply an AED in a hypothetical future cardiac arrest situation.

A larger proportion were able to identify an opioid overdose (38%) and knew to administer naloxone. The majority of people were aware of naloxone kits but only 16% were willing to administer the life-saving drug. Most people were open to the idea of receiving full naloxone training.

Unexpectedly, one in four study participants said that they had previously witnessed a cardiac arrest or opioid overdose.

“Our results show that many people are willing to intervene but they don’t have the necessary training to know when their help is needed. This means we need to think about more focused ways of educating people on how to recognize these emergencies.” — Dr. David Barbic, CHÉOS Scientist

“Our results show that many people are willing to intervene but they don’t have the necessary training to know when their help is needed,” he explained “This means we need to think about more focused ways of educating people on how to recognize these emergencies.”

Although many of the people interviewed were willing to receive training in CPR, they cited time and money as a barrier to attending first aid classes.

The survey also asked whether people were willing to view 1-minute videos about recognizing overdose or cardiac arrest while waiting in line at banks, airports, and other public areas. The overwhelming majority of people were supportive of this idea.

“Resources focused on training bystanders will be of little use if people cannot recognize these emergencies,” said Dr. Barbic. “There is a need for diverse, repeated opportunities to train people on when to act.”

Dr. Barbic is a Clinical Assistant Professor in the UBC Department of Emergency Medicine. Co-authors on this project include CHÉOS Scientists Drs. Jim Christenson, Frank Scheuermeyer, Brian Grunau, and Andrew Kestler. The work, published in Academic Emergency Medicine, was supported in part by funding from the St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation.