A simplified framework could reduce drug expenditures by up to one billion dollars per year

Canada has the third highest drug prices in the world, behind only the U.S. and Switzerland. Since 2015, Canadian policymakers have proposed to change how they set the maximum prices of new patented medicines, which currently cost about $18 billion per year. Despite warnings from the pharmaceutical industry, research from Advancing Health Scientist Dr. Wei Zhang and Director Dr. Aslam Anis has shown that the updated regulations didn’t negatively affect access to new drugs. They also showed that a simplified, evidence-based update to the framework could further reduce expenditures by up to one billion dollars per year.

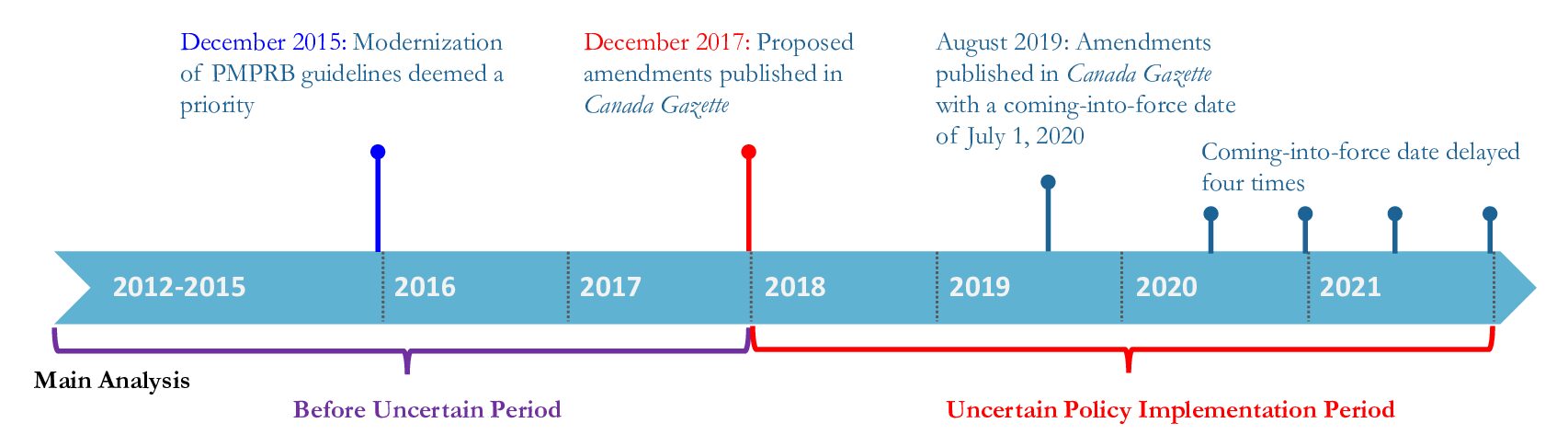

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is the agency that regulates the prices of patented medicines in Canada, ensuring that prices are not excessive. The agency sets the list price (the prices as shown in a list issued by the manufacturer) of new medicines based on the prices in a set of comparable countries or on the prices of similar medicines in Canada. The PMPRB’s pricing framework includes two key instruments: the regulations and the corresponding guidelines. Guidelines help industry understand the regulations and explain the price review process. Proposed changes to the regulations were published in 2017 and after lengthy consultations with stakeholders, were further revised and came into force on July 1, 2022.

As part of the amendments, the U.S. and Switzerland were removed from the list of comparator countries and more similar peer countries with lower drug prices than Canada were added, like Australia, Norway, and Spain. A court challenge from the pharmaceutical industry during this interim period forced the removal of another amendment that would have required the disclosure of the final selling price, which is often less than the list price due to confidential rebates and discounts that manufacturers offer to drug insurance plans.

Did new regulations scare away drug companies and limit public access to drugs?

Tighter price regulations and lower expected drug prices can hinder access to new medicines due to launch delays or new drugs not being launched altogether. However, the impacts of regulatory changes within a single country are not well understood. Drs. Zhang and Anis, along with Advancing Health Statisticians Daphne Guh and Dr. Huiying Sun, Dr. Paul Grootendorst from the University of Toronto, and Dr. Aidan Hollis from the University of Calgary, analyzed the launch of new patented medicines in Canada during this period of regulatory uncertainty.

While the study, published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, specifically looked at the period before the framework officially came into force, Dr. Zhang, the study’s lead author and Program Head for Health Economics at Advancing Health, says that this analysis suggests that the amendments didn’t negatively affect new drug launches.

The researchers compared the difference in the drug launches before (2012–2017) and after the proposed amendments were published (“the uncertain period”, 2018–2021) in Canada to the U.S. and to 12 other countries as a group, the countries the PMPRB currently uses or has proposed to use for price comparison. They looked at whether a new medicine was launched in each country within 2 years of its global launch (the first sale date in the countries analyzed).

The change in drug launches between the two time periods were similar in Canada and the other 12 comparator countries as a group. There were fewer drug launches during the uncertain period, both in Canada and elsewhere, which might have been due to the COVID-19 pandemic or because of the types of drugs that were being developed during this time.

As with many pharmaceutical pricing analyses, the perennial outlier in the findings was the U.S.: for medicines with major therapeutic benefit, the proportion of drugs launched in the U.S. increased while it decreased in Canada and the 12 comparator countries. While this raises questions about the reasons behind this difference, Dr. Zhang says that one of the reasons could be more and more new medicines of this type are so-called orphan drugs, ones used to treat rare diseases that can come with an incredibly high price tag that require complex funding decisions.

The timeline of the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) regulatory amendments (adapted from CMAJ)

Although the U.S. is no longer used as a comparator country under the new framework, the research team felt that it was important to include the U.S. in their study because patients and health care providers in Canada are more likely to be aware of the availability of new medicines in the U.S. and may wonder why certain medicines are in the U.S. but not in Canada.

“In Canada, we often compare ourselves to the United States, but their drug prices can be extremely high, so it’s not an ideal benchmark,” Dr. Anis said. “This paper is an early indication to policymakers that the proposed amendments didn’t negatively affect drug launches in Canada; the change in the number of new drugs during this period in Canada is in line with our comparator countries.”

Despite this reassuring result, Drs. Zhang and Anis say that there are still some questions about what will be included in the final pricing guidelines, and what effect they will ultimately have.

Room for improvement: Simplified framework could save millions

Although the new regulations came into effect last summer, the updated guidelines are not finalized. The interim guidelines remain in place while the final guidelines are still under consultation and development. In an April publication in Health Policy, the team noted several shortcomings of the current and proposed approach that could have different financial implications.

Under the existing guidelines, for drugs that offer substantial therapeutic improvement, the price ceiling for a new drug is set using the higher of the highest domestic price of the substitutes (internal referencing) and the median of the prices in the now-updated list of 11 countries (external referencing). Breakthrough drugs — those with no comparable substitute — are priced using external referencing only.

Under the existing guidelines, for drugs that offer substantial therapeutic improvement, the price ceiling for a new drug is set using the higher of the highest domestic price of the substitutes (internal referencing) and the median of the prices in the now-updated list of 11 countries (external referencing). Breakthrough drugs — those with no comparable substitute — are priced using external referencing only.

The PMPRB has assumed that external referencing would be used for most medicines and reduce expenditures. However, Dr. Zhang says that this isn’t necessarily the case, because drug prices in Canada are so high and many medicines would be priced using internal referencing. “Even if external referencing is used, because companies tend to launch new medicines later in countries with lower prices, the price ceiling could still be high if these drugs have only been launched in the relatively higher-priced countries,” she added.

To test the potential effect of new regulations and proposed guidelines, Dr. Zhang and team looked at patented medicines that were launched in Canada between 2013 and 2018 and sold for at least three years after their launch. Actual drug expenditure for the 400 new patented medicines during this period was $7.13 billion. Applying the new framework, internal referencing would be used for most new products and expenditures would have only declined by 0.7 per cent ($49 million). If external referencing alone was used, expenditures could have declined by 14 per cent ($1 billion).

“Using the median price of the comparator countries, a very simplified and straightforward approach compared to the current method, could have a more significant effect on list prices of new drugs,” said Dr. Zhang. “Unfortunately, the PMPRB has not disclosed whether they plan to use the highest price of the comparator countries, or the median.”

The most recent consultations on the guidelines showed different opinions on this pricing structure from stakeholders.

“I am not surprised by the disagreement. If you ask industry, they would likely choose the highest price option, but payers or insurers would likely choose the median,” she added. “Consultation is important. But when you end up with no consensus, the decision should be based on the ultimate goal of the framework.”

An important caveat about this work is that the final price paid to drug manufacturers remains confidential, so the analysis likely overestimates the effect of changing the guidelines. However, this pair of studies can help policy makers understand the practical consequences of regulatory changes and inform the finalization of the new guidelines.

Both studies were funded by CIHR.